Roth Conversions in Retirement (A Case Study)

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the three tax landmines to watch out for in your retirement plan:

1. RMDS,

2. the “widow’s penalty”, and

3. beneficiary taxes.

If a significant portion of your retirement savings is in traditional IRAs or pre-tax 401k accounts, then you need a strategy to address all three. With proper planning, Roth conversions can neutralize all three tax traps. What follows is a case study to illustrate their utility.

We’re going to look at Jack and Diane: two American kids who grew up in the heartland, moved to the big city, and did their best. Now, they’re ready to retire to Charlottesville, VA, where Jack played football at UVA (they thought he would be a football star, but his knee had other plans… Life goes on!).

Basic Financial Assumptions:

Jack (64) and Diane (63) never considered themselves wealthy. They worked hard, saved diligently, and invested those savings over the years. They managed to put their two kids through state colleges and paid for their daughter’s wedding. Diane still can’t believe they built up a nest egg of investible assets totaling $2.5 million.

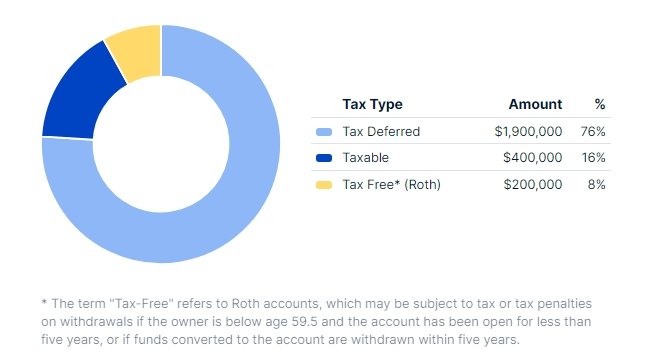

Tax Allocation

Most of their assets are in tax-deferred retirement accounts built up over years of contributing to 401ks and Traditional IRAs. These “pre-tax” assets total $1.9mn and make up 76% of their investments. The rest of their investments include $400k in a taxable brokerage account and $200k in their combined Roth IRAs. For a refresher on these three basic account types, see Asset Location, Location, Location - By Oakleigh Wealth

Tax allocation

Investment Allocation

Their accounts are all invested in well-diversified, low-cost index funds, allocated approximately 60% to stocks and 40% to bonds. Historically, a portfolio like this has returned an average of 7.9% per year, or about 5.7% above inflation. We’ll use this historical average and straight-line returns for our analysis, but their actual returns will vary, and the sequence of those returns will matter a lot, too.

Income Plan

After looking at their historical spending patterns and their financial resources, we determined that they could meet their goals on a monthly budget of $10,000 after taxes ($120k annually) with annual increases to keep up with inflation. Initially, they will fund this entire amount from their portfolio; however, once they turn 70 and receive their Social Security benefits, they will decrease their portfolio distributions by the amount they’re receiving from Social Security to maintain the same level of after-tax spending needs. The prime years for executing larger Roth conversions are the next 6-7 years before Jack and Diane apply for Social Security benefits.

Roth Conversion Analysis

We’re going to look at the impact of two distribution strategies:

Strategy 1: Taxable, Tax Deferred, Tax-Free

Under this strategy, Jack and Diane will withdraw funds from their taxable brokerage accounts first, then from their tax-deferred retirement accounts. Finally, they will withdraw from Roth accounts only when those pre-tax accounts are exhausted.

Adopting this strategy has some attractive positives: very low tax obligations early in the plan when most of their taxable income will come from long-term capital gains. This strategy also allows their tax-free accounts time for continued compound growth. Most likely, they won’t need to tap their Roth funds, and they’ll be able to leave them to their kids.

The downside is that this strategy exposes Jack and Diane to the large RMDs later in the plan, requiring them to distribute (and pay taxes on) more income than they need to live on, which will come in higher tax brackets.

Strategy 2: Roth Conversions to the 24% bracket

This strategy follows the same order of operations as the first, with the addition of executing Roth conversions each year to fill up the 24% tax bracket after funding their $120k per year living expenses. In 2024, the 24% bracket tops out at a taxable ordinary income of $384k for married couples filing jointly, which means we’ll be able to do some very large conversions in the early years, much of which will be taxed at rates lower than their marginal bracket as we fill up the 12% bracket, then 22% bracket first.

There is no maximum dollar amount of Roth conversions we could execute in any given year. You could do it all in one year, but additional converted amounts would be taxed at the 32% bracket, then 35%, then 37% as you fill up each bracket. By spreading the conversions over multiple years, we can ensure they’ll never pay those higher rates.

Targeting a higher or lower bracket for Roth conversion can be beneficial in some situations.

Let’s cut to the punch line:

Following strategy one is like giving a $600k tip to the government!

Under the first distribution plan (Taxable, Tax-deferred, Tax-Free), Jack & Diane would pay $1,275,000 in estimated federal and state taxes over their expected lifetime in today’s dollars. Their average tax rate is 18.4%.

By executing Roth conversions up to the top of the 24% tax bracket, I estimate they will pay $644,000 in taxes with an average tax rate of 11.2%, a savings of $631,000 in today’s dollars. Put differently, by not executing a tax-smart distribution strategy, I estimate that Jack & Diane will be “tipping” the government more than $600k!

So my question to Jack and Diane is, “What would you do with another $600k in retirement?” Even if you don’t need that money, imagine the difference it could make in your children’s lives as they start their own families. Or maybe there’s a charitable organization or cause you care about.

(Don’t) tip your tax-collector!

Why are Roth conversions so beneficial?

There are two reasons: RMDs and the enormous benefits of investing in Roth accounts.

Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs)

RMDs are mandatory withdrawals that retirees must take from their tax-deferred retirement accounts starting at age 73. Each year thereafter, the percentage you’re required to distribute increases. The increases may start gradually, but by your late 70s/early 80s, RMDs can push you into higher tax brackets and trigger additional taxes on Social Security benefits and higher Medicare premiums. Early in the plan, Roth conversions shift money from your tax-deferred accounts, eliminating or greatly reducing RMDs.

Total estimated taxes include ordinary tax, LTCG tax, NII tax, Medicare IRMAA, state, and local income tax. We further assume that the Trump tax cuts expire in 2026 and we revert to the higher brackets from pre-2017.

Roth vs. tax-deferred accounts

With traditional retirement accounts, the government effectively has a lien on the value of your account. In exchange for being able to deduct contributions from your earnings when you were working, Uncle Sam has become your business partner. Under current tax law, he owns anywhere from 0%-37% of the value of your account, depending on how fast you make distributions and for what purposes. What’s more, as your tax-deferred investments grow, so does the government’s portion!

The key to creating a good Roth conversion strategy is choosing to pay your taxes upfront when you’re in a lower tax bracket. Once your funds are moved to the Roth account, all the future growth belongs to you. Typically, retirees find themselves in a much lower tax bracket early in retirement than when they were working (or will be once RMDs kick in).

You can reap these benefits well before retirement whenever your income fluctuates. It’s not that saving in a Roth account is always better. Roth is superior if your rate is lower, a wash if the same, and inferior if your rate is higher relative to your future tax bracket. You can take advantage of this arbitrage by doing Roth conversions whenever your income is lower (early in your career, between jobs, or in down markets). See To Roth, or Not to Roth - by Oakleigh Wealth for more on this topic.

All calculations and projections utilize a 5.7% inflation-adjusted, straight-line return.

The benefits of Roth conversions are likely understated

This analysis makes the following assumptions that likely make the benefits of the Roth conversion strategy understated:

No changes to current tax law: This analysis assumes no future changes to current tax laws. What direction do you think tax rates will go in the future? If you think they’ll go up, then the benefit of Roth conversions will be even greater.

No widows penalty: This analysis assumes both spouses live until the end of the plan. If one spouse dies sooner, the second spouse will incur what’s known as the “widows penalty.” Tax brackets for individual filers are smaller than for married filing jointly, meaning more RMDs will come out at a higher tax rate. See the second of three tax landmines.

No beneficiary taxes: This analysis does not include taxes that will owed by beneficiaries. Anyone who inherits a pre-tax account will owe taxes on distributions at their own marginal income rate. This will likely be during their peak earning years, potentially pushing those distributions into a higher tax bracket. The beneficiary of a Roth account will not owe any tax on distributions; moreover, they can continue to let the account grow tax-free for up to 10 years. See the third of three tax landmines.

Additional Considerations

The role of taxable accounts: To maximize the benefits of Roth conversions, it helps to have some taxable savings. The largest benefit occurs when clients can use their taxable savings to fund their living expenses and the taxes associated with the Roth conversions. Without taxable savings, the client must use some of their retirement account distributions to pay living expenses and taxes. These additional distributions are taxed at ordinary income rates and limit the room for Roth conversions in a given tax bracket. Conversely, investments in a taxable account benefit from lower long-term capital gain rates and don’t count as ordinary income.

It’s usually optimal to keep some pre-tax savings: This analysis assumes we convert everything to Roth, but this is rarely optimal. It’s usually a good idea to maintain some tax-deferred retirement balances. This will create smaller RMDs distributed in the lowest tax brackets (12%-15%). Additionally, pre-tax funds can be used for medical or long-term care expenses, which are fully deductible if they’re over 7.5% of your AGI. Pre-tax accounts are also ideal for charitable giving in Qualified Charitable Distributions (which can offset RMDs) or as bequests after you’re gone. The goal usually isn’t to eliminate all pre-tax amounts but to manage the average tax rate to which the distributions are subjected.

Your results may vary. This is one simplified example for one specific couple. The optimal Roth conversion strategy depends on many factors, including your mix of savings account types, balances, income sources, and spending needs. There are also many important factors we cannot know beforehand. With all financial planning, this is an exercise in making assumptions and trying to model an uncertain future (tax law, investment returns, health, longevity, family, and the stability of the Western/democratic/capitalist world order, to name a few!) Uncertainty is the only certainty.

The bottom line

With tax-smart distribution planning in retirement, you can exert considerable control over the timing and amount of tax you will pay. If you need help with figuring it out, you’re not alone!

I love this stuff, but I realize that not everyone cares about understanding all the nuances. If that describes you, it’s likely worth your time to find a trusted financial advisor to analyze and execute tax-smart distribution strategies so you can reap the benefits and then live your life!